Authors:

Published:

How do you make the invisible visible? This is the central premise of The Cloud, a project that I’ve been working on as a technologist in residence at LIL. The idea originated as a visual joke about the cloud: the vaporous metaphor we use to describe the distributed servers that host remotely-run software and infrastructure.

Initially, I was curious about the effects of the applications and services LIL runs (see this post for a more detailed look at the cost of Perma.cc), and thought it would be interesting to visualize when users were interacting with one of our apps. From there the idea grew and melded with my other interests: what if, rather than just notifying us that users were interacting with us, we could be reminded of something specific, such as the carbon emissions of an action? What would that look like?

Obviously, it had to include a cloud. And when do you see clouds? In a thunderstorm! What if a cloud emitted little lightning strikes every time someone created a Perma Link?

That seemed a little too hard. What if instead, it rained?

I pursued this idea a bit, finding resources to create a smart water pump that I could program to respond to our API. But I hesitated–all that water around all those devices–the idea seemed too wet to execute.

What if we found a way to represent rain that wasn’t literal rain? That could work. We could use LEDs, and program them to look like rain was falling every time someone created a new link.

This seemed like a physically reasonable project, but it wasn’t quite hitting the mark. Why was the cloud raining every time someone hit our API? What did that have to do with carbon emissions and climate change?

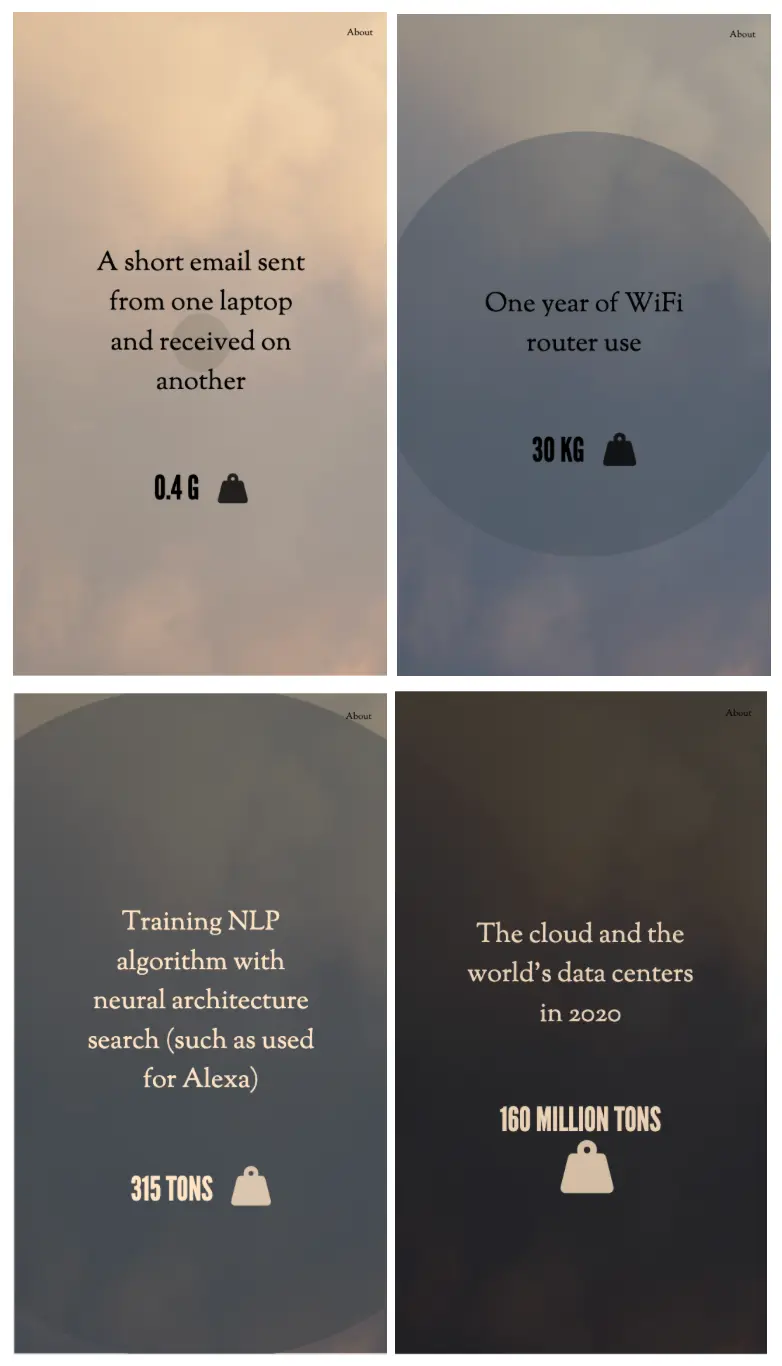

Instead, I decided to simplify the conceit. A user scrolls through various digital activities (such as a Google search or mining bitcoin) and their associated carbon footprints, culled from various sources.

The cloud responds by growing at each step, until it ultimately explodes.

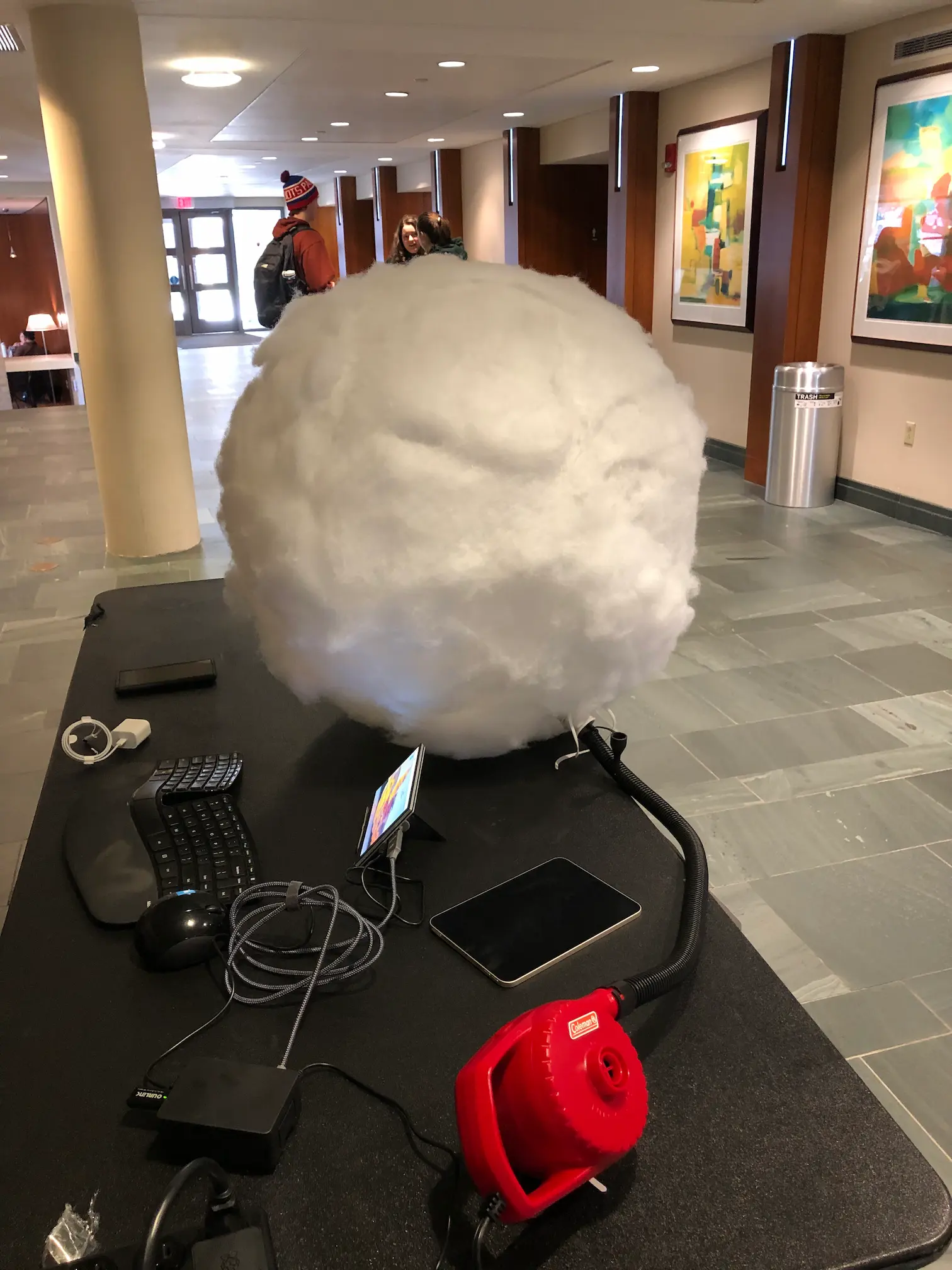

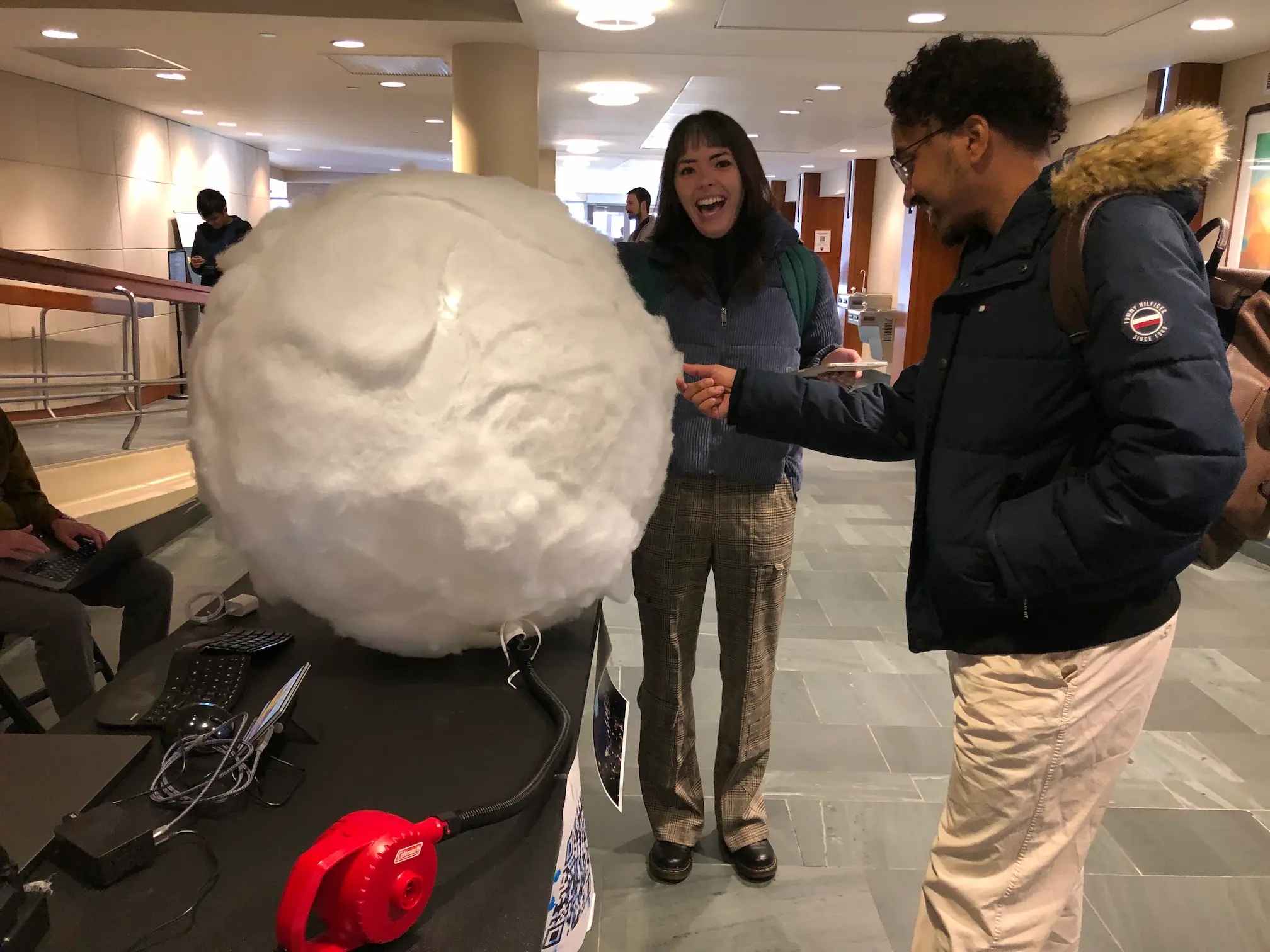

I was lucky enough to be able to try it out on students, staff, and faculty at Harvard Law School’s Caspersen Student Center.

Running the pop-up events provided invaluable insights. Some users were shocked and said that they had never previously considered the carbon impact their digital lives might have. There were those who were simply delighted by the project and found the cloud itself a relatively benign presence. Others found the cloud and its conceit somewhat terrifying–especially as it grew larger and appeared to be on the edge of bursting. Many wanted to touch it, and most wanted to know what steps they could take to lower their personal footprints. This is a tough question to answer given that the sources of impact are so diffuse, but some suggestions include extending the life of your electronics and avoiding passive consumption. Putting pressure on companies to reveal the environmental impacts of their products could also be an effective tactic because having that information would enable users to make more informed choices about their purchases. The takeaways from the pop-ups confirmed my suspicion: that this is an area ripe for further education.

I hope to bring the Cloud to other locations (such as libraries), to continue to use it as an education tool. The code itself is available in a GitHub repo with instructions for how to build the cloud attachment for anyone who wants to create their own.

Special thanks to:

- Amitabh Shrivastava

- Ben Steinberg

- Greg Leppert

- Tal Nagourney